Kelly, Mr Joseph

Joseph Kelly and son, teachers both

Joseph the elder was born in Sydney in 1833, the son of Edward and Ellen Kelly. He pseudonymously came to notice in 1862 when Queanbeyan's Golden Age newspaper published a poem by 'The Bushman'. In the following year he advised Age readers that he was not the Joseph Kelly arrested for drunkenness, being himself a teetotaller, to which the newspaper added that he was a 'respectable and intelligent young man formerly in the employ of Mr. Rutledge' of Molonglo.

He married in Sydney in 1864 and shortly thereafter returned to the district, finding employment as bookkeeper-storekeeper. Although a thoughtful man and a keen debater, his advice was to speak or write only when one thoroughly understood the subject and to stick to the point in dispute; an opponent's introduction of extraneous matter only strengthened one's own case. His versifying continued on a variety of themes, including family loss with which he and his wife Sarah Jane were altogether too familiar. Two of their children, one called Mary, died in 1866.

"In a lonely, village burial ground,

One sunny, summer's eve I stood,

Beside a grassy, moss-green mound,

In pensive, melancholy mood.

A little loved one slept below

The matted, deep-green sod,

Who long had left this world of woe

For the mansions of her God.

A single rose-tree bloomed beside

My little darling's grave,

While in the quiet eventide

Sweet flooding fragrance gave.

The sun sank low towards the west,

And still I lingered near

That little grave – the place of rest

Of my dark-eyed Mary dear..."

Following three months' teacher training at Yass he was sent to Tuggeranong, where a provisional school had operated since 1870 in a slab hut built by voluntary labour on land owned by [Martin or Andrew] Pike. In provisional schools, government regulations allowed for an hour's religious instruction each week, to be given to each denomination separately by the teacher or visiting clergymen. Kelly was just doing his job in 1876 when Father McAuliffe of Queanbeyan saw an Anglican prayer book in the schoolroom and threatened to throw it into the fire. Kelly in turn threatened to take him to court. McAuliffe complained to Pike who took the priest's side. Whereupon Kelly refused to teach the Catholic children, Pike expelled the school, which closed, and Kelly was temporarily transferred to Weetangera.

The authorities took note, and in 1880 promulgated Regulation 76 under the Public Instruction Act. "The Teacher ... shall see that the religious books employed in the Denominational Classes are confined to the time and place of Denominational instruction, and not left in the way of children whose parents may object to them."

As reported by Samuel Shumack, Kelly was bitter about the incident: "My wife and I had a hard time. There is plenty of religion in the world, but very little true Christianity. I am a Roman Catholic and there are men in the Church that are a disgrace to it or any church. But for one of these so-called priests of God I would not be here [Weetangera] today".

The experience did not seem to dim his sense of humour. He was even capable of poking fun at his own poetry:

"Neath the shade of giant gum trees,

In these hot November days,

When the fields are filled with yellow sheaves,

And the Post with doggerel lays."

Kelly's next appointment was to Spring Creek (later Euralie), about nine miles from Yass, where he successfully prepared himself for examinations that gained him promotion to classification IIIA in 1880. From 1886 to 1889 he taught at Murrumbateman, and then at Mulwala. Mulwala was a demotion for a IIIA teacher but Kelly retained his £180 salary. Twelve months into the appointment he was 'severely censured for severe and unjust caning of a pupil' and cautioned. At inspection in 1891 his pupils were found to be 'inefficient' and the Minister authorized his removal to a smaller school. This was Tarcutta on the Sydney-Melbourne line, where he remained until retirement in 1900. In 1896 he was given permission to employ his daughter Elizabeth as sewing teacher.

In spite of the father's experiences, his oldest surviving son followed him into teaching. In 1889 Joseph junior was posted to Pudnam Creek near Rye Park. A generation had passed but some things remained the same: for three years the family had to put up with appalling accommodation.

"The present structure is in a most dilapidated condition, and is not worth repairing. The slabs and bark of which it is constructed formerly did duty as a selector's hut, but was about 7 years ago pulled down and brought here, and re-erected, so that the material has been in use about 15 years. The bark is decayed and swarms with insects, and besides it shifts with every wind and readily admits the rain. It is useless to try and make the place comfortable, as in wet weather all my furniture gets destroyed, notwithstanding the fact that I try my best to patch the roof and keep the rain out. The house contains 2 rooms, the bedroom being only 7 foot long and 12 wide".

The department built young Kelly a new four-room teacher's residence but he was less successful than his father in pursuit of promotion. He sought leave to attend the midwinter 1892 examinations in Yass with a view to upgrading his teaching qualification to IIIA. The inspector noted that his present IIIB ranking was provisional because of practical skills that were not good enough 'to warrant examination' for promotion. The application was not approved.

Nine months later a sequence of events plunged young Kelly's family and school alike into crisis. His only child, Myra May, contracted diphtheria and died. Parents of pupils, fearing contagion, refused to send their children to the school. After a week or so Kelly was able to persuade some of them that their children would not be at risk but before the school could reopen another case was reported. That kept the children away for another fortnight. The Chief Inspector expressed no sympathy for either Kelly or the panicked parents but did allow that 'non-operation' of the school was permissible in the circumstances.

Joseph Kelly junior's next posting was to Carrathool near Narranderra. His parents retired to Redfern, where Sarah died in 1913. Joseph Kelly senior survived her by six years.

Kelly at Murrumbateman

"Following his arrival, Mr Kelly wrote to the Department complaining that 'Mr Grieve still retains office of teacher......Brettell is in the residence and I have been com- pelled to store my furniture etc. in the weathershed'. During this trying time Mr Kelly stayed with the McClung family at 'Hawthorn'. Brettell [his predecessor] had remained in the residence, with the effect that the new teacher had nowhere to live.

Further problems developed when Mr Kelly reported Mr Brettell for non payment of school fees for his children. An abusive letter was written to Mr Kelly by Mr Brettell for report- ing the arrears.

Tragedy struck the Kelly family in April 1888 when their son, George, who was l8 and a pupil teacher at Narrandera, died suddenly. Only a month later another member of the family developed the highly contagious disease, diphtheria, which forced the temporary closure of the school. In August, Mr Kelly felt driven to write that 'he was in fear of being killed or crippled', by the falling plaster from the ceiling of the residence. Messrs Thomson and Bates effected the sundry repairs, and replaced the plaster with pine".

Clarence Dyce replaced Joseph Kelly in 1889.

[extract from D Mulholland, Far away days, Ch 8 Murrumbateman school]

Church versus State

Underlying the educational debates of the nineteenth century was a struggle between the churches and the state for control. The position of the churches was simple; they wished to control the education, particularly the religious education, of their parishioners and they wanted the state to pay for it. The position taken by colonial governments was more nuanced; initially they had no objection to merely subsidizing denominational schools, which were a comparatively cheap means of investing to obtain the public benefits of education. They increasingly faced, however, conflicting demands from the various denominations and arbitration of these became politically contentious, particularly after the advent of responsible government. In the end, the state responded by taking full (although not exclusive) responsibility for universal education which was to be 'free, secular and compulsory'.

One of the significant steps along this road in NSW was the Public Schools Act of 1866. State aid was available to 'Certified' denominational schools with enrolments of 30 or more but there was also a loophole for smaller de facto church schools: where there were at least 15 pupils but fewer than the 25 that would justify a public school, private citizens could make application for a 'provisional' school. Parents would provide the building and government would pay the teacher. The word provisional signalled that in time and with numbers such creations would become Public Schools but some denominations saw this interim arrangement as an opportunity. Local boards could be stacked by one church or another and in spite of governmental inspection and regulations that were supposed to ensure that all faiths had equal access, some provisional schools were locally regarded as 'belonging' to a particular church.

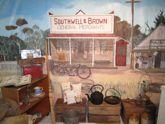

In the Canberra area the tensions inherent in the arrangement surfaced at Tuggeranong in 1876. Joseph Kelly, the teacher, was a Catholic but had arranged with the families that one hour of religious instruction would be given to children of each denomination, as allowed by the Act. When Father McAuliffe, visiting from Queanbeyan, saw an Anglican prayer book in the schoolroom he threatened to throw it into the fire. Kelly threatened him with legal action should he do so. McAuliffe complained to (Martin or Andrew) Pike, the Catholic owner of the schoolroom site, who supported the priest. Kelly refused to teach the Catholic children, Pike expelled the school (although the slab schoolroom and teacher's residence had been built by voluntary labour) and Kelly was temporarily relocated to Weetangerra. Tuggeranong School did not reopen for eighteen months, at another site where the building continues in use to this day as a school museum.

According to Samuel Shumack, a usually tolerant Protestant, if the hand of God was anywhere to be detected in this sorry tale it appeared to have fallen on the Catholic partisans: a year later Pike disappeared and was found drowned; his son Thomas was killed by a fall from a horse; and three years later Father McAuliffe was found drowned in six inches of water, into which he had apparently collapsed while taking a drink from a stream.

Schools

- Tuggeranong School

09/1874 - 06/1876 - Tuggeranong School

10/1876 - 11/1876 - Weetangera School

Relieving, 11/1876 - 02/1877 - Euralie

'Spring Creek', 02/1877 - 04/1883 - Euralie

05/1883 - 05/1886 - Murrumbateman School

05/1886 - 11/1889