< Early Canberra Government Schools

Yass Aboriginal School [1930 - 1951]

Aboriginal schooling at Yass, 1880 - 1910

The 1880 Public Instruction Act made school attendance compulsory for all children from 6 to 14 years of age, and when the Aborigines Protection Board was established in 1883, Aboriginal parents were encouraged to send their children to school.

In April 1883, 16 children from various local Aboriginal camps presented themselves at Yass Public School and were enrolled. However, a meeting of the non-Aboriginal parents objected to the attendance of Aboriginal children and threatened to withdraw all their own children if the Aboriginal children weren't excluded. On the matter being referred to the Minister for Education, the Yass school principal was instructed to expel the Aboriginal pupils in response to objections raised about their health and cleanliness. An alternative, the minister suggested, was that their education could be provided at the Aboriginal stations at Warangesda and Maloga – respectively west of Narrandera, and near Moama, by the Murray River.

Accordingly, all the Aboriginal children were expelled. On the initiative of the Reverend Dean O'Keeffe however, they were accepted into St Augustine Catholic boys' school, in separate accommodation whilst a special 'Yass Black's schoolroom' was built in the grounds. On 12 October 1883, its foundation stone was officially laid by the Dean at an assembly of over 200 pupils from the two convent schools and St Augustine's. Completed in December, it was described as 'a neat compact brick building on stone foundation'.

The Department of Education's ruling on Aboriginal schooling at Yass in 1883, laid the basis of a policy broadly upheld for more than 50 years. Briefly put, it favoured separate education if a sufficient number of Aboriginal children warranted establishing a school especially for them; or else they could attend a normal public school provided 'they are habitually clean, decently clad, and that they conduct themselves with propriety both in and out of school'. In practice, however, this meant that any parental complaints about newly enrolled Aboriginal children invariably resulted in their exclusion from a mainstream public school.

With respect to Yass, once the Board of Education was informed that Aboriginal children had been accepted into a Catholic school, it was considered pointless to open an Aboriginal school to fulfil state responsibility for their education. As a result, St Augustine's was for many years the sole provider of Aboriginal schooling at Yass, though in some small communities away from the town, at Blakney Creek for example, at least some Aboriginal children attended local public schools without complaints being made.

The move to Edgerton Aboriginal station, 1910-16

An Act passed by the government in 1909 enabled the Aborigines Protection Board to remove any Aboriginal people - defined as having 'the appearance of Aboriginality' – from reserves and camping within or near any reserve, town or township. So empowered, the board in 1910 prohibited all Aboriginal camping close to Yass and compelled those living there – or at least all who could be rounded up – to move to a new Board-managed reserve at Edgerton, 12 miles out of town.

Edgerton was modelled on the long-established Aboriginal stations of Warangesda, Maloga and Brungle (near Tumut): that is, a managed, farming community with its own school overseen by the Department of Education. As was customary on Aboriginal stations, it was expected that the appointed manager would also be the schoolteacher, or if married, his wife. Since another school was called Edgerton, the station's school was renamed Mundoonan when it opened in 1911. For a year, the old station's detached kitchen served as a classroom while a new school was built on its own two-acre block adjacent to the manager-teacher's homestead. The small weatherboard building with a brick chimney was ready for use in March 1913.

This extract from a school inspector's report provides a rare glimpse of Aboriginal classes at Mundoonan:-

'The school is at present held in a portion of an old kitchen. It has only been established this year. The children are neat in appearance and regular in attendance. A good deal of drawing is done in the early stages. Chats upon natural facts form the nature work and a good deal of knowledge is shown. Civics and morals, simple stories and Scripture stories are told and fairly remembered. Sewing is neat and useful'.

(Trove: Jerilderie Herald & Urana Advertiser , 25 July 1913)

In June 1915, Edgerton's manager Herbert Hockey transferred to another Aboriginal station at Macleay River. J H Howard, who replaced him, held the position for only a year before Mundoonan School closed in June 1916. By the end of that year, the station also closed and was sold by the Aboriginal Protection Board. As the Aboriginal Protection Board reported in December 1916, over the year the number of residents at Edgerton had averaged 22, but by the end of the year 'there were only 9 half-caste aborigines on the station'.

Edgerton Station was founded with good intentions but failed in practice. Aboriginal people there returned to Yass to be closer to the town's services and paid work, and less strictly controlled. It remained to be seen whether their children would again be restricted to segregated schooling.

Back to fringe dwelling at Yass, 1920s

Not long after Aboriginal camps on the outskirts of Yass were closed in 1910, their former residents, from Edgerton and elsewhere, trickled back to their old sites at Riverside camp on the north side of the town. Makeshift shanties were erected, women found domestic work in well-to-do homes, men did itinerant bush labouring and/or rabbiting; and as previously, at least some children attended the Catholic convent school, separately taught in the 'Yass Black's schoolroom' founded in 1883.

As typical with fringe dwelling, the Aboriginal residents coped with poverty, lack of running water, insanitary toilets, frequent sickness and occasional drunkenness and fighting. By the mid 1920s, the size of the main camp and its location near the town's water supply had given rise to numerous complaints, but no action could be agreed upon between Yass Council and the Aborigines Protection Board to address the problem. In 1925, for example, the female mayor led protests against relocating the camp away from Yass - as attempted at Edgerton - in defence of the town's reliance on Aboriginal women for domestic work: the matter being widely reported as follows:

'Great anxiety is felt among the coloured residents of Yass, many of whom are full-blooded aboriginals, at the decision to remove them from the present mission camp to make way for the water supply reservoir. About 150 coloured residents are affected. The female portion are engaged in occupations in the town, and if removed any distance their means of livelihood will be gone. An influential petition, headed by the Mayoress, is being signed by the women of Yass, asking that homes be found for those affected near the town. It is hoped the Aborigines' Protection Board and others interested in the welfare of the aboriginals will move in this matter'.

[Trove: Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, 17 April 1925]

Near the camp, the Methodist church's Aborigines Inland Mission had erected a small, unlined corrugated-iron building to conduct Sunday services for the Aboriginal population, the leading missionary of which was a Miss Price. At the Mission's annual conference in 1927, Miss Price explained that no progress had been made on the unsatisfactory Aboriginal situation due to an all-round lack of responsibility. As the Cootamundra Herald reported (on 26th May): 'Miss Price (said) it was shameful to realise that although the aborigines were the original owners of the country, no land could be found for them. They had no place in the district to go to. The women of Yass wanted them to be near the town because they were helpful in domestic duties, such as laundry and other household work, but the men, it appeared, wanted them driven away.'

On the matter reaching state parliament, Chief Secretary Albert Bruntnell claimed that the government had spent enough on Edgerton and that any new measures to eliminate the town's Aboriginal problem had to be initiated by the Council: -

'I might point out, that several years ago the Board spent over ₤2000 in the establishment of a properly organised station for Yass aborigines at Edgerton, 10 miles out of the town. Numbers of dwellings were erected, including a school, and a teacher-manager placed in charge. The aborigines refused to remain there and left, the place closed, and the buildings sold at, of course, a big loss. The Council then allowed these people to form the present camp. I would further point out that the Council has ample powers to prohibit the erection of insanitary buildings, and it also has the power to demolish the camp.'

[Trove: Gundagai Times & Tumut, Adelong & Murrumbidgee District Advertiser, 20/7/1928]

Yass Aboriginal School, 1930

Nearly fifty years after Aboriginal children were first excluded from Yass Public School, the same complaints arose against twelve who were attending the school in 1929. As reported in both local and Sydney newspapers, at a P & C Meeting on 21st June a letter objecting to the Aboriginal pupils had been presented to the headmaster, Mr James Brigden. Speaking on the matter, one parent said that it was not 'the colour to which they objected, but the prevalence of disease at the blacks' camp', as reported by the government medical officer. Another parent pointed out that Aboriginal pupils in the local Catholic school had always had a separate schoolroom. The meeting had decided to protest to the Education Department, and urge that a provisional school be opened at the camp. (Trove: Sydney Morning Herald, 22 June 1929)

Such a sensitive racial issue evoked a quick response from the Minister for Education, David Drummond. Referring to the protest letter, he said the matter would certainly be investigated, adding that the general practice was for Aboriginal children to attend schools provided for them on reserves. Since school attendance was compulsory by law, the Department of Education acted quickly. It was arranged through Miss Price that the Aborigines Inland Mission building (previously mentioned - at the northern end of Grand Junction Road) be used on weekdays as an Aboriginal schoolroom.

Early in January 1930 the 'school' was made ready. Inspector C E Hicks had surplus furniture from a closed school at Euralie sent by rail: 4 moveable desks of large size, 6 feet 8 inches long with matching trestle forms, and 2 desks and forms of smaller size. Classes commenced the same month; about 20 children attending, though rather irregularly. The first teacher, Miss Eva Hagan, taught for two years in this unlined corrugated-iron building. There is no recorded complaint that she had to use a petrol can toilet in a nearby parents' hut; as in its first years the 'school' had no lavatories for either the pupils or teacher.

Despite a strong complaint from Inspector Hicks that the Aborigines Protection Board

find a more suitable building as a matter of urgency, nothing progressed. Eva Hagan's replacement, Miss Phyllis Osborne, took over on 2nd February 1932, pending a satisfactory inspection later that month. In his report, Hicks reiterated the building's deficiencies: no running water, no lavatories, cramped and uncomfortable interior, no outside fencing and no shade trees. The barren site, he added, gave 'very little opportunity' in the form of a garden, though 'something is being attempted'. Miss Osborne was doing her best under difficult circumstances, he reported, the pupils were suitably controlled and with a few exceptions demonstrated a willingness to learn. The report concluded: -

'The teacher is endeavouring to awaken the interest of parents in the school, but with limited success ... effectiveness of efforts is minimised to some extent through the position of the school room, surrounded as it is by homes of parents – thus nullifying the teacher's influence. Housing conditions too are disheartening. Nevertheless brightening methods are adopted & hopeful progress is anticipated...Earnestness of purpose is undoubted ...there is much to commend & the school is in suitable hands.

- Cont'n of award of "B" is recommended'.

(This and following quotes are from 'Yass Aboriginal School', NSW Records, 5/18262.2)

Miss Osborne's trials and tribulations, 1932-33

Periodically over six months Miss Osborne complained about the lack of a teacher's lavatory, and in time both her health and morale began to suffer under such trying conditions. The Protection Board did try to secure funding for an Aboriginal reserve, houses and school to the west of the town, but this lapsed due to the government's financial straits during the height of the Great Depression. Then in July 1932 a Board inspector - having visited the school without prior notice given to Miss Osborne - sent a report to the Education Department criticising her suitability as a teacher: -

'Miss Osborne does not in my opinion reach the standard required of Teachers by this Board for the following reasons: -

1. Her personal appearance would lead one to believe that she was one of the

Aborigines themselves. Her clothing was to say the least filthy, and looked as if it

had been thrown on rather than fitted. Shoes might have been polished at some

time, but certainly did not show any sign of polish at the time of my visit.

2. Poor if any personality

3. I should say from observation no control over the Children.'

The report concluded with the Board inspector's recommendation that the Department also arrive unexpectedly, as such a visit was required 'to see Miss Osborne in her usual attire'. But on the matter being referred to School Inspector Hicks, he declined to concur, saying of Miss Osborne: 'Although not by any means pre-possessing nor approaching modern attractiveness, she was clean and tidy (in) appearance' and that 'her personality, although not strikingly forceful nor vivacious, appeared of an average type and certainly not such as to condemn her for the work in which she is engaged'. Inspector Hicks was taken at his word: a superior's final remark was that 'no further action be taken'.

In November 1932 the school was closed due to Miss Osborne's ill health. As a doctor's opinion connected her sickness with the lack of a school lavatory, Inspector Hicks made a determined request that the matter be urgently addressed by the Protection Board: 'To have to put up with the unsatisfactory school-room is trying enough, but it is surely most inconsiderate to expect a lady teacher to continue under conditions considered detrimental to her health for reasons indicated. Distance from place of residence is approximately ¾ mile. Recommended that A. P Board be approached again on this matter and unless a satisfactory convenience be erected within a reasonable period, say within a fortnight, the teacher be withdrawn'.

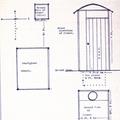

This ultimatum finally achieved some action from the Protection Board. In January 1933, Yass builder Joe Vallance's tender to construct a teacher's toilet for ₤6.10.0 was accepted and a pit-closet type was erected before school resumed in February.

Unfortunately for Miss Osborne, just as one challenge at the school was resolved another arose. Two weeks after school resumed in February, a parent claiming to represent others wrote to the Aborigines Protection Board complaining about Miss Osborne's proficiency, in particular regarding her recent absences and the time spent on outdoor lessons such as swimming in the river. The Board, having previously sought Miss Osborne's dismissal the year before, sent the complaint to the Minister for Education, who referred it to Inspector Hicks to investigate. By then it was a serious matter, and on February 18th the inspector wrote to Miss Osborne quoting the parent's letter at length. He requested a full copy of her weekly timetable of lessons together with an explanation on how closely it was being followed.

Miss Osborne promptly complied, vigorously defending herself. It was true, she said, that due to sickness she had taken two days leave, and had applied for it properly. The outdoor classes, she reported, had consisted of the usual weekly swimming lesson and a few lessons one afternoon in the shade by the river: -

'The morning had been a very trying one for both the children and myself. The heat was unbearable. It was impossible to obtain any results from the children, eighteen of whom were crowded into a space 12' x 12' of a corrugated iron building. It has been the worst day this Summer during school hours ... On Tuesday, 14th Feb., I took the children on ten minutes walk up the river where they were able to have such lessons as did not necessitate the use of writing materials, in the cool. They lost absolutely no time because of this arrangement because the two and a half hours allowed for recess and lunch were occupied in lessons The children took their lunch which they were allowed twenty minutes to eat. We returned to the school at 2.40 p.m. for Roll Call'.

Miss Osborne added that she had invited nearly every parent to voice their complaints, but as none were made, it appeared that only one parent had been critical. Appended to her report were the upper and lower division timetables and a supportive parent's note, saying in part: 'I was very anoid (sic) about the report that was put in the Board about you ... and will be very sorry if you leave us because you are a lady with feeling'.

In the same mail on 20th February, Miss Osborne wrote a separate letter to Inspector Hicks stating that while the new toilet was an improvement, she could no longer tolerate the lack of a water tank, the unbearably hot classroom and the school's surroundings: 'The environments of the school, to say the least of them are disgusting. On two sides of the school is a rubbish dump. The school is practically surrounded by the hovels in which the children live. I am enclosing the report presented by the Government Medical Officer to the Council'. The letter concluded that since 'efficient teaching is impossible under the prevailing conditions', she had notified the Protection Board of her decision to resign on Thursday 9th March.

Inspector Hicks replied immediately, stating that the Department also required a letter of resignation, by return post. In reply, Miss Osborne wrote that she had decided instead to resign that day - Friday 3rd March, adding: 'I have left the keys of the school, press and lavatory in the custody of the local Inspector of the Police'.

On Miss Osborne's resignation being received by the Education Department, a marginal comment noted that there was 'no risk of her readmission because the APB are not likely to be satisfied with her, and she had no standing except as a teacher of an aborigines school'.

Last years in the old school building, 1933-34

Miss Osborne's replacement, Margaret McAulay, had an unfortunate accident two months after her appointment to the school. On 5th May 1933, attempting to replace a curtain on one of the school windows, she fell heavily to the floor when an old chair she was standing on collapsed. A local government medical officer, Dr R J English, advised that she take some sick leave. However after a week of her feeling weak and dizzy he suspected a brain haemorrhage, and had her admitted into Yass Hospital. She was hospitalised 18 days in Yass and a further 27 days in Sydney Hospital - having travelled to Sydney by train in the care of a nurse. As Dr English had reported the matter early on to the Government Insurance Office, both doctor and patient were anticipating that all her medical and travel costs would be covered by worker's compensation.

After more than six weeks' absence during which the school was closed, Miss McAulay returned to work on 27th June. Two months later she was notified that worker's compensation had been refused by the Government Insurance Office: it was deemed that her extended incapacity 'was not due to an injury sustained in the course of her employment with the Department'.

Better news was that steps towards establishing a new Aboriginal reserve and school at Yass were at long last progressing. In May 1932 the Aborigines Protection Board had acquired a site on the opposite side of the town, but funding to develop it hadn't been forthcoming. Then in February 1933, matters came to a head when Dr English informed Yass Council that Aboriginal camping so close to the town's water supply posed dire health risks: -

'The dwellings are composed of petrol tins built into shanties, floored with earth. Most of them are very dark inside, badly ventilated and totally unsuited to human habitation. They should be condemned. The sanitation closets are built of petrol tins...and open petrol tins were used as pans...flies were swarming everywhere. The contents of the pans are buried on the hillside... and heavy rain would wash the excreta into the river. ...This state of affairs is a disgrace to and a menace to the health of the community. An outbreak of enteric fever with its attendant mortality will surely come'.

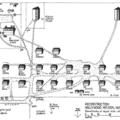

Urged on by this, work on the new site commenced in 1934. On the acreage purchased earlier at the end of Rossi Street, on the western fringe of the town, scarce Depression funding was used to build an unlined corrugated-iron school and a cluster of small houses for the residents. The buildings were basic but all had water tanks, fireplaces and pan toilet outhouses. Teacher and pupils transferred to the new school on 1st December 1934. The area was fenced, gardens were cultivated and even an area levelled for a tennis court. Officially it was Yass Aboriginal Reserve, but being such a salubrious improvement on camp life the residents called it 'Hollywood', and the name stuck.

The new school on Yass ('Hollywood') Reserve, 1935-51

In June 1935 Miss McAulay informed Inspector Morrow that a measles outbreak had resulted in many absences, reducing the attendance at one stage to only a single pupil. Three months later, the inspector achieved some much-needed improvements to the school after reporting its various deficiencies: -

'The new school building erected for the children of Yass Aboriginal School is constructed mainly of tin & is unlined ... it can be understood how cold it is in winter & how hot on hot days. ... Moreover the fireplace smokes so badly it is not wise to light a fire in it. I consider that a better type of fireplace should be constructed'.

After three difficult years Miss McAulay left the school in December, replaced by Mrs Ella Campbell-Hiscocks in January 1936. The new teacher may also have had a nursing qualification because she took on the dual role of teacher and matron. After a month at the school she applied for a petrol allowance, stating that the trip to school by car was two-miles uphill from her residence in Adele Street. This was declined, however, due to six miles daily travel being the minimum mileage claimable.

The next teacher, Elizabeth Gillespie, seems to have become over involved in reserve life to the detriment of her teaching duties. In March 1937, a Protection Board inspector found that her 'tactless and unnecessary interference in domestic disputes' was resented in the Aboriginal community. She was 'haphazard' in controlling bullying at the school, he reported, and appeared to ignore advice. On the day of inspection, only 11 pupils were present out of 26 enrolled, and when the children were told to play outside so that he could talk with her 'I cannot say that I made much progress as Miss Gillespie had an uncontrollable desire to acquaint me with her past history in various branches of Missionary work', he complained.

The first male teacher, Donald Bailey, served nine months in 1938; the second, Eric Arthur-Mason, taught for five months in 1939. Of passing interest is that Arthur-Mason's sewing teacher, Miss Phillis Soloman, recorded her home address as 'Hollywood, Yass', and when Arthur–Mason applied for leave to attend a military training camp, he was identified by the Protection Board itself as the teacher at 'Hollywood via Yass': indicating that the reserve's light-hearted label became its regular name during the 1930s.

In his 2011 memoir Ngunnawal elder and Yass community leader Eric Bell reflects on his time as a pupil at the school from 1946 to 1950:

"....there was a school for Aborigines on the Hollywood Reserve within easy walking distance of my home........ I remember the Hollywood school well from when I was six. It was an unlined, one room affair, and it was some time before toilets were built for the teacher and the kids. The school only went to grade 4, but all four grades were housed in one room, between twelve and twenty kids..........My first teacher in 1946 was Miss Grace Emily Tester...Miss Tester was succeeded at Hollywood by Norman Gilchrist [1948 - ed], an enthusiastic man who tried to make school an interesting and happy place......He was highly innovative and amongst other things tried to encourage sound shopping practices in the girls by setting up a make-believe store, complete with empty packets of grocery staples. The girls loved playing at shopping and shop keeping. Nature study and sport were also big on Mr Gilchrist's agenda and I remember how he use to encourage us in both activities. It was not all work though, as he would take us down to the Yass river for swimming in the summer months, to cool off. Each morning before going into the classroom, we had a respectful flag-raising ceremony, and perhaps surprisingly, sang 'Advance Australia Fair' and even more surprisingly 'The Maori Farewell'." [Bell, 2011 p.42]

Another highly respected elder of the Ngunnawal people and Foundation member of the Ngunnawal Elder's Council, Agnus Shea has also recalled her schooling at Hollywood.

In 1949 Yass Council accepted a proposal by the Aborigines Board to begin integrating Aboriginal people within the community, assisting the process with subsidised housing. Yass Aboriginal School on Hollywood reserve closed in June 1951, followed by the reserve itself in 1955. By then, Aboriginal children were at long last being accepted in mainstream schools throughout the state.

References:

- Bell, Eric. Looking back. My Story. Privately published, Yass, 2011 (grateful thanks to Tony MacQillan for permission to quote)

- A synopsis and timeline of Aboriginal education in NSW : NSW Aboriginal Education Timeline 1788-2007

- Kabaila, Peter, Aboriginal camps around Yass Canberra Historical Journal, 69, 2012, pp 12-19.

[This entry on Yass Aboriginal School was contributed by Keith Amos, former teacher at The Mullion School out of Yass]

Location Map

Teachers

- Hagan, Ms Eva Penelope

01/1930 - 12/1931 - Osborne [Martin], Mrs Phyllis Edna May

01/1932 - 04/1933 - McCaulay, Ms Maragaret Christina

03/1933 - 01/1936 - Campbell-Hiscocks, Mrs Ella Ada

01/1936 - 08/1936 - Gillespie, Ms Elizabeth May

10/1936 - 03/1938 - Bailey, Mr Donald William

03/1938 - 11/1938 - Tester, Ms Grace Emily

12/1938 - 02/1939

05/1941 - 07/1947 - Arthur-Mason, Mr Eric Hubert

06/1939 - 11/1939 - Herbert, Ms Elsie V

11/1939 - 05/1941 - Bissell, Mr Thomas G

07/1947 - 05/1948 - Gilchrist, Mr Norman

05/1948 - 01/1959 - McKelligan, Mr Neil

04/1951 - 06/1951

NSW Government schools from 1848

- Yass Aboriginal School (external link)

< Early Canberra Government Schools

If you are able to assist our work of identifying, documenting, and celebrating the early bush schools of the Canberra region, please contact us or .