Rediscovering Ginninderra:

Edward Kendall Crace

Born: 1844; Died: 1892; Married: Kate Marion Mort

Known as the 'squire of Ginninderra', Edward Kendall Crace was a controversial figure in the district. Undoubtedly, he was a very successful farmer and made an important contribution to the prosperity of the district and became a very wealthy man, but he was litigious and readily clashed with residents if they got in the way of his economic interests.

Crace was born in London in 1844 into a wealthy family of interior designers who enjoyed a number of Royal commissions. His father, John, owned the family's decorating business, Crace and Sons. His mother was Sarah Jane Hine.

Crace was not interested in succeeding his father in the decorating business and was apprenticed as an engineer. After a horse riding accident he decided to recuperate through a voyage to Australia on the ill fated Duncan Dunbar in 1865. This ship was wrecked off northern Brazil with the 117 passengers managing to all reach the precarious safety of a sandbank on a reef, where they waited until their rescue some days later. It was in these dire circumstances that he first met his future wife, Kate Marion Mort, who had been returning to Sydney with her mother and sister. The thirteen-year-old girl acted stoically and cared for her younger sister during the disaster.

Back in England, young Crace continued working as an engineer, spending time in Manchester and Russia. But in 1869, undaunted by the wreck of the Duncan Dunbar, he decided sail again to Australia, this time on the Great Britain.

In the colony, Crace renewed his acquaintance with the Mort family, who were woolbrokers and pastoralists. He married Kate in 1871. They had nine children. He purchased a share of a the family's Toowoomba station and helped manage it, but Crace did not feel at home in Queensland and soon sold up. His personal correspondence shows that he was critical of the egalitarian nature of the social structure of the colony and the success enjoyed by emancipated convicts in Queensland civic life.

In 1877 Crace briefly returned to England. But he was soon back in Australia. This time he took up a position with William Davis (junior) on his Palmerville estate and his new Gungahlin homestead as a manager of both properties. But Crace fell out with Davis. Fortunately for both parties, Davis was keen to sell and Crace purchased these properties; taking over as the new 'squire' in 1880.

Davis was an excellent pastoralist and had built up Palmerville estate and his other holdings into a model farming and grazing operation. Crace was similarly talented as a pastoralist and the two estates flourished under his control. He amassed a substantial fortune over the years and added a large twin-gabled extension to Davis' Gungahlin homestead (then known as Gungahleen) in the early 1880s. He also even added a third property, Charnwood station, to his holdings. In total, Crace was running over 8,000 sheep (mostly merinos but some Leicesters as well), almost 700 Devon cattle and 90 head of horses on 20,000 acres. He also had a 1,400-tree orchard planted and built a miniature lake and ornamental gardens.

Although he actively supported the community through his patronage of events and participation in community groups (e.g. Canberra Railway League, Stone Hut School board, etc.), Crace won few real friends amongst the local Ginninderrans. He had a very clear view of what his position should be in society and resented the very different approach in the colony. He also sought an English education for his children and returned to holiday there himself on occasion. It would appear that he did not feel 'at home' in colonial society.

Edward Crace was also an advocate of the position of the large landowners and actively worked against the interests of the many smaller and struggling farmers of the district. He challenged access to water, closed common roadways passing through his properties and disputed the location of his borders with neighbours. He argued with the Boyds and Wrights and fought legal actions with the Holland, Dixon, Ryan, Boon and Maloney families. In 1881 Thomas Gribble pulled down one of the fences, which the litigous Crace had erected, barring an established roadway to his property. At first, Gribble was unsuccessful in court facing charges of trespass and was fined the sum of ₤44. However, Gribble won a subsequent court case in 1885 – again concerning an attempt by Crace to obstruct access to The Valley.

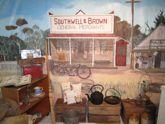

In 1884 he lost a case in which David Boon (jnr) successfully sued him for ₤140 owing for the clearing of briars at the Charnwood estate. Crace had recently acquired Charnwood (1881), adding it to his vast holdings at Gungahleen and the Ginninderra estate. There was an agreement that Boon would clear the estate's 3,500 acres of briars (the worst being close to the Charnwood homestead) within three years. In return he would receive ₤280 and be granted 50 acres on which to live and cultivate for himself. Crace alleged that the work had not been completed by the due date. For Boon, a line of eminent local graziers and farmers supported his claim that the work had been completed and was 'unusually well done' - William McCarthy, James McCarthy, Philip Williams, Samson (Snr) and Samson Southwell, Ellis Smith, and Robert Johnston (Jeir). The jury was offered, but declined the opportunity to go and view the land in question. 'The jury retired and after a short absence returned into court with a verdict for plaintiff for ₤140'.

[Queanbeyan Age 3 December 1884}

Despite this record, Crace was not always unsympathetic to the plight of the free selectors. Albeit in a comparison with Charles Campbell of Duntroon (who took a much harder stance), Samuel Shumack reports that Crace was relatively generous to his father, Richard Shumack, in allowing him access to water during drought.

In the economic downturn of the early 1890s, like many other pastoralists, Crace struggled to keep afloat and to maintain his large interest repayments (annually ₤3,600). Nevertheless he had built up a large revenue stream through careful management of his large wool clip and beef herd and he was in a position to recover quickly.

In September 1892 Crace and his groom, George Kemp, drowned tragically in an attempt to cross the flooded Ginninderra Creek. Although the accounts of his death vary in the detail it would seem that Crace had urged his coachman to try an unsafe crossing, as he was impatient to return home and even took the reigns from the coachman himself. When the coach became trapped in the creek, Kemp swam out to calm the horse but was injured and went under the rising waters and was trapped in roots where he drowned. Crace remained in his seat, but it was not long before the coach was also swept away, before help could arrive and he too drowned. He was aged 48 years.

His widow, Kate, struggled to keep the estate together, although it is thought that she was heavily assisted through her family and its connection with Mort and Co. She died in 1926 in Woollahra.

Related Photos

References

- Coulthard-Clark, C., 'Gungahlin Revisited', CHJ, no. 26 (1990) pp. 26-34

- Gillespie, L. L., Ginninderra: Forerunner to Canberra, Campbell, 1992

- Meyers D. (ed. K. Frawley), Lairds, Lags and Larrikins: an Early History of the Limestone Plains, Pearce, 2010

- Shumack, S. An Autobiography, or, Tales and Legends of Canberra Pioneers (ed. J. E. and S. Shumack), Canberra, 1967

- Various editions of the Queanbeyan Age and Goulburn Evening Penny Post